Taking Summer Seriously

How the Summer Matters campaign is changing the course of “Expanded Learning” in California.

During his first few years of elementary school, Miguel Mena spent his summers mostly on the couch. A shy kid growing up just southeast of Los Angeles, he would watch TV or play video games with his little brothers. His great-grandmother cared for the boys while their parents worked, but taking active young kids to the park or a museum was often more than she could handle. Things changed dramatically in third grade when Miguel’s mother, Victoria Rios, heard about the Whittier City School District summer program.

Whittier was no typical remedial summer school with worksheets and worn textbooks. Miguel and his friends spent their days reenacting scenes from science fiction books, working on group projects, or leading hands-on lessons for their peers.

Summer school at Whittier is part of a trend in California to improve access to high-quality learning when children are traditionally out of school (after 3 p.m. and in the summer). Advocates say these “expanded learning” options are vital for low-income children at risk of falling behind.

Summer school back in the day “was more like tutoring,” says Becky Schultz, Whittier’s director of expanded learning. “And it really didn’t work, sitting there all day long in a math class. It’s really changed now, and I hope we never go back.”

Unlike some of his peers in neighboring districts, who saw summer school as a punishment for poor performance, filled with vocabulary quizzes and math worksheets, Miguel came home talking about books and begging his mother to make the healthy meals he had learned about in cooking and gardening. He didn’t want to miss a single day.

“We’re trying to create an opportunity for kids that falls in between the boring remediation model of summer school and the kick-up-your-heels fun and carefreeness of a summer camp,” says Katie Brackenridge, senior director for expanded learning initiatives at the Partnership for Children & Youth, an Oakland-based nonprofit that advocates for afterschool and summer programs. “It’s that sweet spot—called summer learning—where they’re having a great time and at the same time they’re intentionally learning something through those activities.”

The Whittier program was part of 12 communities whose new programming was supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation under the Summer Matters campaign. Thanks to Summer Matters and advocates around the state like Brackenridge, awareness of the importance of high-quality summer learning is growing. Districts in California are experimenting with summer school models designed to engage kids in a more hands-on way

And Victoria Rios says the approach works. Miguel “was a little shy and wouldn’t open himself up to teachers if he had a problem,” she says. “Now I see so much confidence. His grades started going up.”

Why Summer Matters

Louann Carlomagno says educators in her district have long been concerned about the achievement gap between low-income students and their more advantaged peers. As superintendent of Sonoma Valley Unified, nestled in the heart of California’s wine country, she says districts like hers across the state are serving a growing population of low-income students, most of whom are dual-language learners when they enter kindergarten. In three of the five elementary schools in the district, 80 percent of the students are English language learners from low-income families.

Educators know that summer school is critical to those students. Yet for them, she says, summer school was all about getting kids more instructional time in the classroom. The notion of “summer learning loss” was not the driving force. “Summer school was because kids didn’t meet their grade-level standards,” she says. “We weren’t trying to be preventive. We were reactive.”

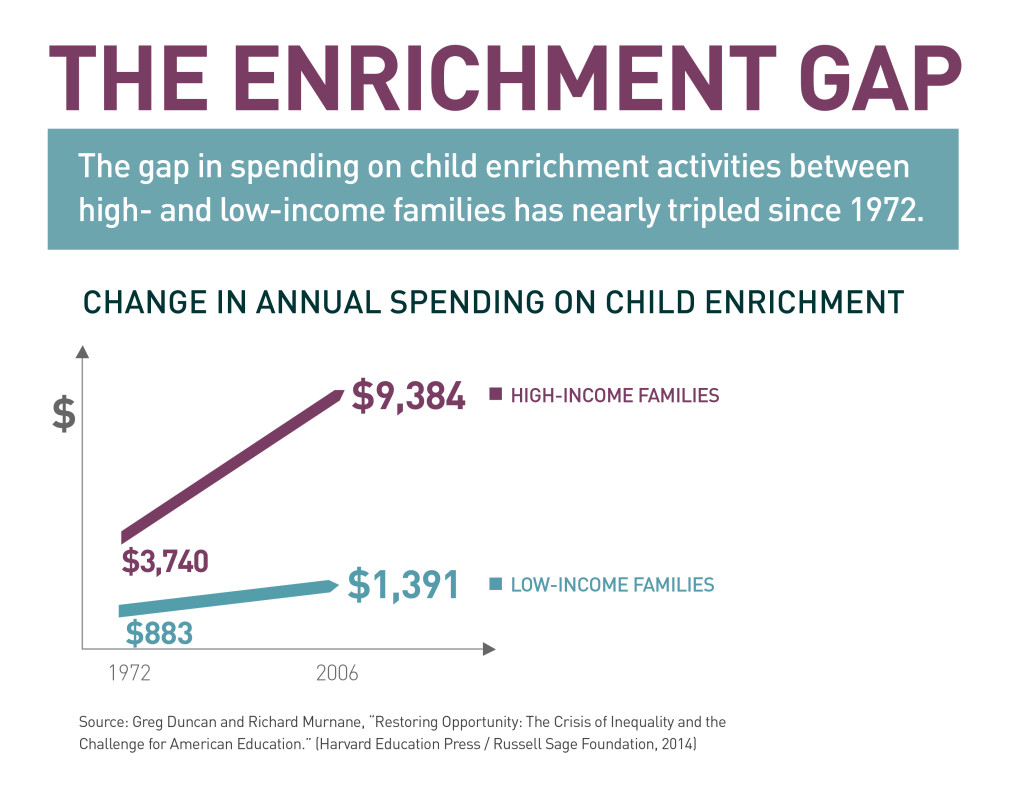

Carlomagno was not alone. Although there was plenty of research on the achievement gap between low- and high-income children, summer rarely factored in as a contributor. But in hindsight it made sense. Researchers Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane have shown that the gap between what higher- and lower-income families spend on their children’s enrichment, from trips to museums to summer camps, tripled in 30 years.

Summer, in particular, was a dividing zone. Researchers in Baltimore found that as much as two-thirds of the 9th grade achievement gap between low- and higher-income children could be traced to summer learning loss during elementary school. In Sonoma, Carlomagno saw this gap emerging first-hand. Tracking students’ progress, she says, educators discovered that the loss in reading skills among those who had not attended summer school was the equivalent of four months of instruction. Meanwhile, those who had attended gained two months.

“Our students from low-income families start school from behind and they never catch up,” says Ron Carruth, superintendent of the Whittier City School District. “Unless we have engaging opportunities for students in the summer, we’re never going to help them close the gap.”

Summer learning loss was a concern of the Packard Foundation as well, as was the quality of summer and afterschool programming. With the Foundation’s support, in 2009 a coalition of educators, policymakers, and families launched the Summer Matters campaign in an initial set of five California communities (eventually expanding to 12). Eager to build on-the-ground models of great summer programming, the stakeholders worked to create high-quality programs across the state that address local needs of children and youth. To support quality, the campaign also funded “technical assistance” providers, a network of experts who help staff in summer programs through training, coaching, program planning, quality improvement strategies, and regular evaluations. To ensure sustainability, it also created an infrastructure of support, with a steering committee and annual group gatherings of staff and technical assistance providers.

Summer Matters “helped us focus our efforts in summer school because before that, we didn’t fully understand summer learning loss and the huge impact on our students,” says Carlomagno. “We always knew summer learning loss existed, but Summer Matters really refined our thinking.”

The March to Higher Quality

When the recession hit in 2008, summer school was often the first to go under budget cuts. It wasn’t long after the cuts took hold, however, that the phones started ringing from desperate parents looking for afterschool and summer programs. “It makes you realize how much need there is, particularly for low-income families,” says Carruth.

David Espinoza, a father of three in Gilroy, Calif., was one of those parents. “A lot of kids don’t do anything over the summer and lose half of what they learn. And summer school keeps them in touch with their friends. Day care is too expensive.”

While the recession was devastating to school districts, it came with a silver lining. It created a “clean slate,” says Brackenridge. It allowed advocates and educators to experiment and build out new models that focused not just on access but on quality learning experiences that would make a difference for low-income children.

Quality in afterschool programs, and by extension summer school, was not something that state policymakers had regularly stressed. Prior to the recession, the state had been devoting more funds to increasing access to afterschool programming but not necessarily to improving program quality. But with the help of Summer Matters, the past five years have seen “a bigger focus on the quality of programming and some very targeted efforts statewide about what quality looks like and its impact on kids,” says Brackenridge.

New leadership at the state department of education in 2012 helped shift focus and led to the introduction of Quality Standards for Expanded Learning in California in 2014. Soon after that, also in 2014, a new state law passed that also put a much stronger focus on quality improvement. These changes came, Brackenridge said, in large part from what advocates and the field learned from the Summer Matters campaign.

“What was wonderful was that the [the Packard Foundation] grant allowed us to challenge some of the previous traditions of summer school as a simple continuation of the academic year,” says Carruth in Whittier. “The Packard Foundation looked at summer learning as a summer camp located on a school campus.” It was strikingly different from the traditional “remedial” approach.

The Foundation knew the shift in focus was neither natural nor easy. One aspect of the technical assistance for staff was a focus on a set of indicators of quality programming, as outlined in the Comprehensive Assessment of Summer Programs (CASP) tool. CASP was developed by the National Summer Learning Association to measure and advance the quality of summer programs in nine domains, ranging from staff to individualized programming to unique program culture. The tool helped Whittier identify areas and approaches for improvement.

“It changed the whole way we do summer school,” says Schultz. With 82 indicators of quality, Shultz says the first year was a tough transition. But the results were worth it. The technical assistance coaches also instilled the notion of a cycle of continuous improvement—plan, train, assess, and reflect—which helped the programs evolve.

One change, at Whittier for example, was to shift from direct instruction—a teacher at the front of the class leading the lesson—to student-facilitated learning, where students direct the lessons and work collaboratively. That model took some getting used to.

“We had to change our way of thinking,” Schultz says. The biggest change came from the teachers, many of whom were veteran educators who had to get used to the kids running the show. “‘You mean we don’t stand up there in front? What are you talking about?’ they’d say. But now those same teachers do it in their regular classrooms during the school day,” Schultz adds.

“We’d never go back to the old way,” she says. “It’s here for good.” That conviction, she thinks, reflects a broader, systemic change that promises to bring more opportunity to more children.

Gianna Tran, deputy executive director at the East Bay Asian Youth Center (EBAYC), another Summer Matters community, says this was the most extensive evaluation that their program has had. EBAYC runs expanded learning programs at several campuses in the Oakland Unified School District. The organization used the CASP tool to alter its pedagogy and improve programming.

Based on early low marks in the “program culture” and “planning” metrics of CASP, Tran says EBAYC developed a summer camp approach instead of a regimented classroom approach. It also individualized the lessons to better align with students’ ages and needs.

Before, says Tran, “Our program was an afterschool program in disguise. We taught writing and called it creative expression. It was extremely boring for the students.” Today, students feel empowered to learn something new and have fun, she says, and the real treat is the three-day camping excursion the kids take to Northern California, led by park rangers. As a result, CASP scores improved from average to “really good,” Tran says, adding: “Students love it. They get excited.” As for staff turnover, it is no longer a problem.

In Fresno, another Summer Matters community, the school district’s new five-week summer program also resulted in impressive gains for students, according to Rico Peralta, director of program development for the Central Valley Afterschool Foundation. Students who had participated in the Summer Matters program were one-third less likely to be chronically absent from school than their peers. Their self-reported academic work habits improved. The programming, which centered on full immersion in a book, including role playing or conducting science experiments inspired by the book, led to improvements in grade-level vocabulary and overall confidence in reading. In a short five weeks, children saying they felt confident in their reading rose from 51 percent to 56 percent.

For Schultz in Whittier, the progress is also evident. On a four-point quality scale, the program advanced from 2.2 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2014 on the CASP. Fully 85 percent of students increased their reading fluency by five words or more, an evaluation found, and 90 percent increased their knowledge of healthy cooking and nutrition, a special focus.

But the real evidence, says Schultz, are in the nonquantifiable elements. The student-facilitated approach, for example, had profound effects. Kids with speech problems, or those who were “very very very shy,” were leading the class by the end of the five weeks of summer learning. “They have the confidence now,” Schultz says. “And that’s exciting.”

In addition, behavioral problems plummeted as kids became engaged in learning, which further convinced the teachers they were on the right track. Kids were saying things like, “This is the way I like to learn” and “I like school again,” says Schultz. “Those kids who had checked out at school, now they were there every day in the summer.”

Not only students benefited. The program sharpens educators’ skills as well, Peralta says, and the excitement over the initiative helps retain staff and improve continuity.

This post originally appeared on David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Stories of Progress