CSBA Guide: Summer Learning Matters

A guide for supporting summer programs for school board members

Imagine students who might otherwise be isolated at home spending their summers:

» Improving their reading skills and content knowledge while gaining confidence as learners

» Having positive learning experiences and leadership opportunities that help them see school as a place where they can succeed

» Being physically active, eating healthy foods, and making new friends

» Stretching their communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creative abilities in a low-stress, lowstakes environment where they feel free to take risks

» Building their social-emotional skills, including self and social awareness

» Engaging with diverse peers who have a range of needs

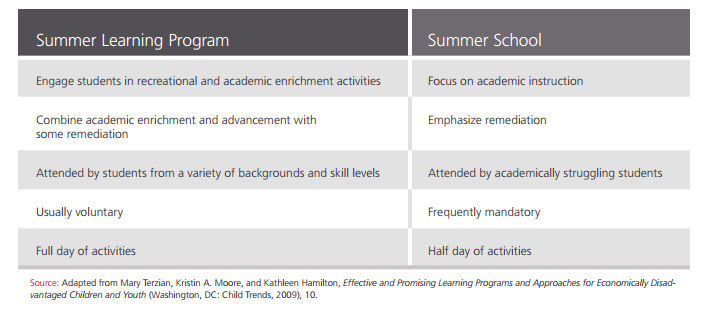

These are the experiences, activities and goals that characterize what has become known as the summer learning movement. Rather than the remediation approach that is often the focus of traditional summer school, summer learning programs blend rigorous academics, enrichment, and project-based learning in activities that motivate and engage students.

Across California, more and more school districts, county offices of education, and communities are embracing summer learning as a more effective way to meet the needs of their students.

This guide is intended to better acquaint school board members and superintendents with summer learning, and to help them establish or expand programs that result in greater learning and enrichment for the students they serve. It includes a description of the summer learning model, information from research on the negative effects of summer learning loss and how the summer learning approach can counteract such loss, examples of some specific summer learning efforts in California, and ideas and strategies for getting summer learning programs started, including funding sources and a sample planning timeline.

The benefits of a strategic summer learning approach can be powerful. It takes planning and vision to implement such programs in school districts and communities — and board members and superintendents are vital to making that happen.

Research shows that summer is often a time of learning loss, particularly for low-income students. Providing these students more time for learning during the summer months is one of the most effective ways to avoid learning loss and enhance students’ progress. Programs that include a broad approach to learning that goes well beyond remedial activities have been shown to be particularly effective.

Effective summer learning programs are anchored in their communities. Summer learning staff proactively seek out and garner tangible support from families, community-based organizations and civic leaders. These partnership strategies enable the programs to maximize resources and provide the best overall experience for youth.

Summer learning programs are not business as usual

Summer learning is a good strategy for all students, especially those in elementary and middle school. While summer learning emphasizes an enrichment approach, students needing intensive remediation and middle school students who need credit recovery, can also receive the academic support they need. In robust summer learning programs these students participate in academic interventions focused on specific skill areas as well as in a broad array of strategies including hands-on, experiential and enrichment activities that reinforce those academic skills.

As the table below outlines, effective summer learning programs meet many of the academic objectives of summer school, while offering students an experience they enjoy and a program they are eager to attend.

Officials in the Kerman Unified School District saw the difference firsthand when they changed the summer program they offered for middle grade students. After taking a credit recovery approach in 2014, and seeing very poor attendance, this Fresno County school district wanted its summer investment to yield better results. District leaders turned to their after-school program provider and the local county office of education, asking them to replicate a summer learning program already in place nearby. In 2015, the district’s 100- student pilot program was filled to capacity.

After that pilot year, Kerman superintendent Robert Frausto said: “I think we’ll double our numbers next year. Kids lose information over the summer and here I have a program that helps them retain knowledge. I think traditional summer school is not working, particularly for middle school. You get kids in a summer program when they want to be there. They’re learning but they’re also having fun. I heard nothing but really positive comments from students and parents.”

Traditional models of summer school can also be necessary and effective. Classes for credit recovery, for example, are an important service that county offices of education and school districts provide, particularly for high school students. However, this traditional kind of summer school should not and need not be the only kind of summer offering.

The summer learning model: focuses on activities that motivate and engage young people, provides summer enrichment experiences (similar to those available to children from higher income families who can pay for them), and aligns with school district learning goals in ways that are intentional and strategic. School districts and county offices of education that operate summer learning programs find that these programs are cost effective, in part because they marshal resources from the larger community and from a range of funding sources.

Summer learning programs share common elements to meet locally driven objectives To meet the particular needs of the students in their communities, summer learning programs differ in their focus, objectives, and the ages of the students they serve. Examples of programs with different emphases include:

» Academically focused programs to improve students’ skills and achievement in areas like math, reading, and science, and promote high school completion and college preparation.

» Enrichment and recreation programs that emphasize new experiences, positive relationships with instructional staff and peers, and a sense of belonging—often focusing on fostering personal, social, emotional, physical, and career-related abilities, such as interpersonal skills, character development, communication, conflict resolution, and leadership

» Career development programs—often for older youth— that promote career decision-making, interview skills, and other job-related abilities that promote employability, economic self-sufficiency, and success

» Programs that combine aspects of all of the above

Although the emphases of these programs vary, they share many common elements. For example they:

» Take place on school sites

» Combine the efforts and knowledge of both certificated and non-certificated personnel, the latter often the same staff members who work in after-school programs

» Provide staff who have strong, positive relationships with students

» Include engaging learning experiences that focus on meeting students’ emotional, social and academic needs

» Are aligned with district goals

Summer learning programs address achievement gaps and student wellness

For children from higher income families the summer months frequently include vacations, camps and enrichment programs related to sports, arts and music. These activities are proven to keep children engaged and learning in measurable and positive ways. Such opportunities are not accessible for many lower-income children whose families do not have the resources to provide for these kinds of summer activities. For children in low-income communities, summer is too often an educational drought that results in losing knowledge gained during the school year. In addition, for many low-income students, summer breaks are also a break from healthy nutrition and therefore, a threat to their health and well-being. Annual California-based studies regularly show that less than 20 percent of the students who were receiving free or reduced-price lunches during the school year were also participating in a subsidized summer lunch program.

Without summer programs, low-income students lose ground year after year

Summer learning loss is the term used to describe the phenomenon of students returning to classrooms in the fall having forgotten some of what they learned during the previous school year. Researchers have been documenting summer learning loss over the last several decades and the evidence of its deleterious effects continues to grow. According to Jennifer Peck, executive director of the Partnership for Children and Youth, “While middle-income children retain knowledge or, in many cases, make gains over the summer, low-income children fall behind.”

Summer learning loss referenced above is not inevitable. There is strong and growing evidence that summer learning programs can counter this trend and improve student success.

The positive impact of summer learning programs is well documented

Evidence from school districts throughout California that have been implementing summer learning programs since 2009 indicates that this model of summer school has contributed to improved student outcomes. Based on this evidence and that from other states, growing numbers of educators and researchers support the expansion and deepening of summer learning enrichment and academic opportunities for children, focusing first on those in low-income or disadvantaged families as an effective approach to closing achievement gaps.

Parents understand the potential of summer as a learning opportunity for their children and indicate strong support for and interest in summer learning programs. A recent survey by the After School Alliance showed that nine out of 10 California parents believe public funding should support summer programs.

Thus, school districts, parents, and communities are looking at summer as an opportunity to expand learning time for students. School and district leaders also consider summer learning an opportunity to provide important professional experiences for teachers and after-school staff.

Program evaluations conducted as part of the Summer Matters campaign looked at academic, social, and emotional outcomes for students and families. Typical results across well-implemented summer learning programs included:

» English language learners demonstrated statistically significant increases in their grade-level vocabulary skills, a gateway to English language fluency.

» Parents who were interviewed in focus groups reported the programs helped their children prepare for the transition from the elementary to middle grades, a period when many students begin to disengage from school.

» Nine out of 10 parents indicated that summer programs helped their children make new friends and get along better with other students, gaining social skills that will help them be successful in school and beyond.

In addition, early evidence indicates that summer learning programs support the approaches to learning emphasized by the Common Core State Standards. A 2013 report on summer learning programs found that young people were tackling complex, open-ended questions; making active choices about their learning; working collaboratively; connecting themes and knowledge across subject matter areas; and honing their communication skills, including public speaking — all goals of the Common Core State Standards.

The Summer Matters Campaign

Summer Matters is a statewide campaign focused on creating and expanding access to high quality summer learning opportunities for all California students. It is a diverse coalition of educators, policymakers, advocates, school district leaders, mayors, parents and others who work collaboratively to promote summer learning in California. The campaign includes coordinated policy and advocacy strategies designed to raise awareness about the value of summer learning programs and inspire high quality programming statewide. The work of Summer Matters’ is showcased in 13 summer learning communities. Summer Matters is an initiative of the Partnership for Children & Youth and several partner organizations.

Summer learning programs have been shown to have a positive effect on social-emotional learning as well. Increasingly, school districts and county offices of education are focusing on ways to strengthen students’ confidence in school and improve their behavior as proven preconditions for academic success. The research shows that desirable academic behaviors like going to class, doing homework, arriving ready to learn, and actively participating in class all contribute to better academic performance. These behaviors are strongly affected by the kinds of skills and attitudes that summer learning programs can successfully nurture.

A report about programs that were part of the Summer Matters campaign described how an intentional focus on social emotional growth paid off for the young people who participated. For example:

» Clear expectations for behavior—coupled with youth development strategies—supported and motivated students

» Offering many different types of opportunities for success nurtured students’ self-confidence

» Clear learning objectives helped students measure their own progress and reflect on whether they had met the objectives

» Turning school campuses into places for learning that were fun and enriching—blurring the lines between school and community—built children’s sense that they “belong at school”

Examples of best practices in summer learning

The summer learning programs being implemented across California reflect the state’s diverse communities and circumstances and the learning priorities set by counties and school districts. The following are just a few examples of the various ways that school district leaders are putting those programs together across the state.

Sacramento City Unified School District

The Sacramento City Unified School District Summer of Service program provides civic education to the 7th and 8th graders in this 47,000-student school district. The program is managed at multiple sites each summer by community-based organizations. The summer staff includes district teachers and employees from its after-school programs. A district level

committee, with site representatives, plans the summer program.

At every site, students learn basic elements of service learning and then apply them to complete a service project they select and design. The activities and focus of the programs vary, reflecting the approaches taken by the program providers, the needs of the students and families at the school, and the priorities of the school site principals.

Fresno County Office of Education

Fresno County Office of Education (FCOE) plays a pivotal role in the planning and management of summer learning programs for many local school districts. FCOE is the fiscal agent for most of the after-school programs in the county and they work closely with the California Teaching Fellows Foundation (CTFF), a local nonprofit organization that hires and provides professional development for college students who work in more than 200 after-school programs in Fresno and Madera counties. Working with local school districts, the two organizations leverage this structure to provide summer learning programs. Reading, leadership, nutrition, and science have been central learning goals in the programs, largely depending on district priorities. Several districts have allocated a portion of their LCFF funds to underwrite facility and transportation costs and to cover the per-pupil fee that CTFF charges in order to pay the program staff.

Mountain View School District

The Mountain View School District in the city of El Monte takes a collaborative approach in which district office staff work closely with partner organization THINK Together, their after-school provider, to create a summer learning program that does double duty, providing a rich summer learning experience for both teachers and students. Students experience a wealth of camp-style activities plus instruction from certificated teachers. Teachers participating in a summer professional development program on the Common Core State Standards get an immediate, hands-on chance to work with students, apply what they have learned, and participate in peer coaching that strengthens their training experience. The district’s long-standing and collaborative partnership with THINK Together helps make this integrated approach work. In summer, the teachers focus on the academic component of the program while THINK Together staff provides a wrap-around program that includes physical fitness and enrichment activities, plus other group activities that create a spirit of summer freedom and fun for students. As one of the state’s largest providers of expanded learning programs, THINK Together contributes multiple resources, such as the curriculum from NASA that was used in 2015 to provide STEM activities in Mountain View. Field trips, including an overnight camping experience, also set the program apart from school as usual. Out of the 7,500 students in this elementary district, almost a third participated in the summer learning program in 2015 and the district is planning to expand that further.

In each of these communities, and in others throughout California, districts and counties have started out by assessing the programs and partnerships they have, with their after-school programs often providing a logical place to start. Integral to the work has been program evaluation based on a clear set of goals and using a variety of methods for measuring success and identifying areas for improvement.

Steps to implement summer learning in your district

Successful summer programs cannot happen without effective leadership and active support from boards and superintendents. Not only does the board establish the vision and goals for the district, it adopts the budget, sets the policies that provide direction and structure, and monitors program effectiveness.

Through all its areas of responsibility, the board can create an expectation that summer programs are part of a school district’s overall educational effort, not just a seasonal offshoot. To achieve this goal, school districts and their governing boards should treat summer learning equally with traditional school year programs and make them part of year-round planning.

In its 2011 report, Making Summer Count, researchers at the Rand Corporation offered six recommendations to school boards for building better summer learning programs:

- Move summer programs from the periphery to the core of school reform strategies through

better planning, infrastructure, data collection and accountability. - Strengthen and expand partnerships with community-based organizations and public agencies to

align and exploit existing resources, identify gaps and improve programs. - Provide budget and logistic information to participating school sites and potential program

partners by March to allow sufficient time for planning and recruitment. - Be creative with funding: use multiple sources.

- Create a summer learning task force consisting of local stakeholders to identify areas of collaboration and planning.

- Change the summer focus from remediation and test preparation to a blended approach of academic and enrichment activities.

Funding Summer Learning

Summer has not traditionally been regarded as a critical learning opportunity but this attitude is changing. Quality summer learning programs not only address the equity issue of summer learning loss but also have the potential to provide important learning progress for all students, both with regard to the state’s new academic standards and to students’ social and emotional skills.

The cost of summer learning programs compares favorably to that for traditional summer school, an important consideration given that limited resources are always an issue for California schools. This cost profile is due principally to the mix of certificated and classified staff members in summer learning programs and to the potential contribution of resources from outside agencies and partners.

There is no singular source of support for summer learning programs: successful programs braid together multiple revenue sources. Securing funding requires planning, persistence and creativity. Some of these sources are described below.

Sources of funding

» The Local Control Funding Formula is one way to support summer programs. These can be a valuable component in any school district’s Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) and an effective use of LCFF funds. Summer learning strategies address multiple state priorities, including improving school climate, increasing student and parent engagement,

implementing state standards and providing access to a broad curriculum. The programs can be targeted to high-priority subgroups and schools, and their impact can be clearly measured.

» 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) federal funds are designated to support establishing or increasing expanded learning activities for K-12 students. They focus on three primary areas: improved academic achievement, enrichment services that complement academic programs, and family literacy. While the majority of 21st CCLC funds are for after-school programs, a small portion of the resources—called supplemental funds—can be used for summer learning programs. 21st CCLC grants are available through a competitive proposal process managed by the California Department of Education (CDE). Eligible applicants include districts and county offices of education; cities, counties, and community-based organizations; public and private agencies, or a consortium of two or more of these entities collaborating with a local district or county office. Applicants must serve students from schools that are eligible for Title I school wide programs, which generally means at least 40 percent of the school’s population is enrolled in the free and reduced-price lunch program. The CDE sometimes reduces the 40 percent requirement when considering other mitigating factors.

» After School Education and Safety Program (ASES) state funds are targeted support for after-school programs. Some districts also have ASES funds (called supplemental) that can be used for summer school. A first step in exploring these funds is to check with the district’s after-school or student services department to find out if the district has this funding and how it is currently being used. Instead of running separate ASES-funded summer programs, many districts have been strategic about leveraging this funding with LCFF dollars to create a more robust summer learning program with community partners, more hours and/or more students. Legislation (SB 429, 2011) created greater flexibility in the way grantees use both 21st CCLC and ASES supplemental funding. Specifically, the law allows grantees to run a longer program, serving a broader variety of students at alternate sites from the funded school sites.

» Title I federal funds assist schools that have high concentrations of economically disadvantaged students to promote student achievement, staff development and parent and community involvement. In recent years, funding restrictions have been loosened and Title I funds have become more widely used to support summer learning programs. Decisions about the use of Title I funds are made at both the school- and district level. Like 21st CCLC funds, at least 40 percent of the students in eligible schools or districts must qualify for the federal free or reduced-price lunch program. Almost all districts in California receive some Title I funding. In addition, districts that receive Title I, Part C, migrant education funding, are required to conduct summer school programs for eligible migrant students. In some communities, school districts, county offices and migrant education programs are coordinating their efforts.

» The Seamless Summer Feeding Option and Summer Food Service Programs provide federal funds that enable districts to obtain summer meal reimbursement funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) when the CDE approves the district as a program sponsor. Both programs are designed to provide meals to children in low-income communities during summer vacation. Seamless Summer Feeding Option funding is available only to districts that also participate in the National School Lunch Program.

» Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) are offered through local government entities to support community services, including summer learning programs, to low- and moderate-income residents. Eligibility criteria vary by locality, and most CDBG funds are awarded to nonprofit and public organizations that support low- or moderate-income individuals. The overarching mission of CDBG funds is to promote viable, successful, thriving communities. In many communities, support for summer programs is seen as part of that effort.

» City or county funds vary widely, both in how they are dispensed and in amount. These are local taxpayer funds and typically represent local priorities. Often this money is used to run parks and recreation department programs that provide recreation, enrichment, and sometimes career and job preparedness activities. School districts interested in broadening a summer school program to include recreation and enrichment can partner with their community’s recreation department. Libraries and state parks have also stepped in as public partners, providing staff support and field trip opportunities. Some cities (e.g., Oakland and San Francisco) designate funds for summer youth programming and contract with local schools or nonprofits to operate the programs.

» Philanthropic foundations have frequently played an important role in supporting innovation like summer learning programs. Numerous foundation and private organizations, large and small, support or advocate for educational goals, which may include summer learning. Eligibility criteria and the degree of financial support range widely. Most foundations have specific funding guidelines, which may include geographic, population or programmatic considerations. The duration of support may be months or years depending on the grant objectives.

» Community partners can be instrumental in gathering support for summer programs. In some communities, partners such as the Boys’ and Girls’ Club use their connections with local businesses and civic organizations to help districts develop stronger private support for summer programs. Some districts also look to private program providers, from yoga instructors to sports camps, to help provide enriching activities that are integral to the on-site summer learning program.

» Summer programs can charge fees if their funding sources do not prohibit them, and if participating families are willing and able to pay. Fees for summer programs are increasingly common, often implemented to cover gaps between other funding and total program costs. They can be one-time up-front fees or be collected weekly or daily, and should include sliding scales to help low-income families. Under state law, entities that receive 21st CCLC and ASES supplemental grants for summer programs can charge fees, but no student can be turned away because he or she can’t pay.

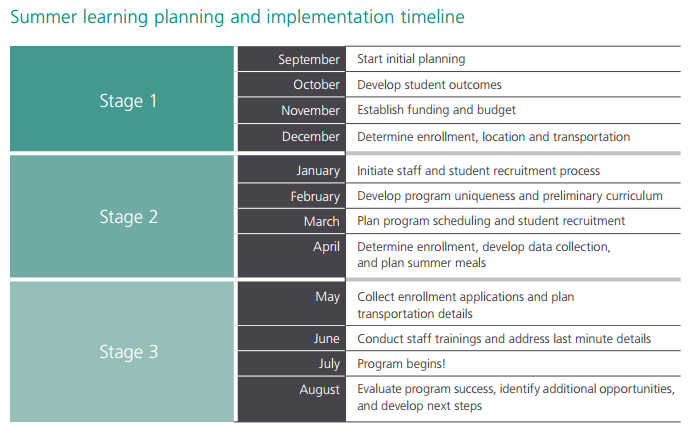

Start planning for summer learning: Important questions for boards

Making successful summer learning happen, as the summer learning schedule in this report describes, requires year-round planning. In addition, by asking pertinent questions, school board members can bring attention to the issue of summer learning as well as insights into how best to use resources to support these programs.

1. What is the scope, approach and funding for the district’s current summer programs? This should include looking at:

» The professional development and planning time staff are provided

» The partners that help these programs operate

» The cost per student

» The revenue sources used for the program, including allocations within the district’s LCAP

» Any evaluations of program effectiveness related to specific district/school goals

2. What partnerships and expertise could be leveraged to support summer learning? When it comes to summer learning, the first experts to tap are often people and programs already working in the district. These might include:

» After-school program providers, for whom combining enrichment and academics is already familiar and whose staff already know the students, families and school site personnel.

» School site and district staff involved in curriculum design, professional development and student supports whose expertise can be leveraged to assure a high-quality program that meets outcome goals and student needs.

» Regional experts, for example from county offices of education, who can bring expertise, perspective and connections, particularly in rural areas or relatively small school districts.

3. What summer programs already exist in the community, particularly programs that provide activities for low-income youth and English learners? These can include programs provided by:

» Local government agencies, such as city parks and recreation departments and libraries

» Community-based organizations such as the Boys’ and Girls’ Club or the YMCA

» Local business and trade associations that may offer internship programs to older youth

» Nearby colleges and universities that may be looking for internship opportunities for their students

» Other school districts with successful programs that might be open to serving more students or sharing their program management experiences and skills

An important strategy for board members to initiate discussion and planning for summer learning is to advocate for a study session to make clear the opportunity that summer learning represents, how it is different from remedial summer school, and why new approaches to summer learning—beyond remedial approaches—are important to consider. Helpful background information, including extensive research as well as examples of summer learning programs operating throughout California, is available on CSBA’s Summer Learning webpage and at the Summer Matters website.

Summer learning works for students

Summer learning loss can contribute to achievement gaps that grow wider over the years: summer learning programs can help stem the growth of those gaps. These programs have a well-documented positive impact on student outcomes. Around the state, districts, county office of education and communities are planning and implementing programs that meet the needs of the students they serve, build partnerships and maximize resources. Governing boards play a pivotal role in this work by setting a vision that embraces the value of summer learning, and by ensuring the support and effective implementation necessary for successful programs.

Click here to add your own text

Summer learning: As easy as 1, 2, 3

The summer learning timeline below offers a comprehensive, month-by-month guide for school governance teams and their staffs to plan, budget, prepare for and operate a successful summer learning program.

Click here to add your own text